|

Dementia is a syndrome

characterized by a gradual onset of symptoms, including memory loss and

decline in such cognitive abilities as thinking and decision making.

Dementia is extremely prevalent in the elderly population, with a severe

dementia affecting approximately 5% of people above 65 years of

age.

Diagnostic features include,

memory impairment and at least one of

the following:

aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, disturbances in executive functioning.

In addition, the cognitive impairments

must be severe enough to cause impairment in social and occupational

functioning. Importantly, the decline must represent a decline

from a previously higher level of functioning. Finally, the

diagnosis of dementia should not be made if the cognitive deficits occur

exclusively during the course of a delirium.

There are many types and causes; the

three major causes of dementia of neurosurgical interest are normal

pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), subdural hematoma, and intracranial mass

lesion. Together, they account for only 3.5% of dementia, most of them

due to NPH.

NPH is discussed in this section.

Normal

pressure hydrocephalus:

NPH

is a state of chronic hydrocephalus in which the CSF pressure is in

physiologic range, but a slight pressure gradient persists between the

ventricles and the brain. There is ventriculomegaly without a rise in

intracranial pressure (ICT) as a result of insidious obstruction of the

CSF circulation due to subarchnoid block. It is also called low pressure

hydrocephalus, occult hydrocephalus, and hydrocephalic dementia. Normal pressure hydrocephalus can be a

reversible or treatable disorder. It is thought to account for about 5%

of all dementias. The incidence is about 1 out of 100,000 people.

Hakim

and Adams first described normal pressure hydrocephalus in 1965.

The NPH syndrome has continued to present many questions with regard to

the most reliable diagnostic and prognostic factors. In addition

the high rate of complications associated with shunting makes treatment

highly controversial.

Etiology:

45%

of the cases are idiopathic and most of the patients are elderly. The

high prevalence of atherosclerotic disease of the cerebral arterioles and

veins vessels has been blamed. Changes in CBF and the CSF chemistry may

play a part. The CSF obstruction may provide the driving force by

establishing a transmantle gradient. The other possible factors are

increased pulse pressure in the ventricles.

The

rest are due to defective archnoid villi. The archnoid villi, and

subsequently subarchnoid pathways, may get obliterated in SAH,

infections, trauma, and intracranial surgery resulting in NPH.

Pathophysiology:

The

exact pathogenic cascade leading to hydrocephalus with normal CSF

pressure and the typical symptomatology is not yet completely understood.

It has been hypothesized that NPH is initiated by an increase in

the ventricular CSF pressure with resulting changes in the tangential and

radial stresses within the brain parenchyma. At first the

ventricular dilatation is small and combined with compensation of the

raised CSF pressure by the compressibility of the low pressure venous

system. As the pressure remains high over hours and days, there is

a net shift of water content from the brain although the water content in

the periventricular white matter increases due to movement of CSF across

the mechanically damaged ependyma under a hydrostatic gradient. The

yielding or plastic deformation of the tissue leads to relaxation of

tangential stresses in the brain parenchyma and consequently to an

increase of subdural stresses. Loss of protein and lipids in the

brain parenchyma occurs due to chronic stress. In this stage CSF

pressure returns to normal values, for instance by decreased CSF

absorption resistance by reopening of previously blocked pathways or new

routes being opened up, or decreased CSF production. The

ventricular dilatation persists due to decreased resistance of the brain

parenchyma. Very small transmantle pressures (2-4 mmHg) are able to

maintain the ventricular dilatation under these conditions.

The

pathophysiology of symptoms in NPH is related to dysfunction of

periventricular structures. This can be explained by the increased

initial tangential stress in this region, the hydrostatic edema which may

occur due to destruction of the ependyma and later on the loss of protein

and lipids. Besides, a pre or coexisting vulnerability of the white

matter caused by ischemia, hypoxia, head trauma and the effects of ageing

may be required for the development of the NPH syndrome.

Clinical

features:

NPH can occur at any age, but is mainly a

disease of the elderly. The occurrence of NPH in children is claimed by

some. Symptoms in children are different from symptoms in the

elderly and include abnormal limb posturing, irritability, and vomiting.

The estimated prevalence among mentally disturbed elderly people ranges

from 0 to 5.6%.

The

important clinical signs are mental changes, urinary incontinence, and

disturbed gait.

Mental

changes:

The

cardinal aspect of the mental change is the slowing of mental processes

without any aberration. Mental deterioration in NPH is due a disorder of

frontal lobe systems which have extensive connections with the basal

ganglia (especially the caudate nucleus), the thalamus (especially the

dorsomedial nucleus), the hippocampus, the amygdale, the cingulated

gyrus, the septal nuclei, and the hypo-thalamus. All these

structures are interconnected by long pathways through the deep white

matter of the brain, most particularly the periventricular regions and

the centrum semiovale. The typical features are a loss of

creativity difficulties with task performance in daily life, poor scores

on tests for formulation and maintenance of strategies, self monitoring

for errors in performance, and ability to ignore irrelevant distracting

stimuli. Problems initiating and sustaining actions may occur. Apathy and

inattention in early stages may precede short term memory deficits.

Akinetic mutism manifests in the late stages.

Gait

disturbances:

Retropulsy,

falling spells, and disturbances of balance may precede a slow, short,

shuffling, wide based, and unsteady gait. The pathophysiology of gait

disturbances is considered to be multifactorial, involving several

periventricular structures such as the corticospinal tract, the caudate

nucleus and its caudatocortical connections with other extrapyramidal

nuclei and the frontal cortex. The gait disturbance is a

subcortical motor control disorder rather than a phenomenon of spasticity

or apraxia.

They

may be bed ridden in the late stages.

Urinary

incontinence:

It

is an important component of the clinical picture. Urge incontinence is

frequently the first sign. The pathophysiology may be related to

dysfunction of the superior frontal gyrus and the anterior cingulated

gyrus. In later stages loss of sphincter control may occur due to

severe frontal lobe dysfunction.

Late

stages there may be faecal incontinence.

There

is no papilledema, but occasionally nystagmus may be seen with increased

tendon reflexes. The primitive reflexes of sucking and grasping appear in

the late stages. Neuropsychological tests of frontal lobe function help

to evaluate the dementia.

Differential

diagnosis:

Occasionally

cerebral degeneration may coexist with NPH and thus present difficulties

in decision making. Some knowledge on other causes of dementia

helps. Dementias can be sub-classified as cortical or subcortical

dementia.

Cortical

dementias often involve aphasias, apraxia, and/or agnosia, and

include, Alzheimer's disease and Jacob-Creuztfeld disease.

Subcortical

dementia is characterized by intact language and visuo-spatial function,

and include Parkinson's, Binswanger’s disease, Huntington’s

disease, HIV infection, and depression.

In

NPH there are no illusions, hallucinations or irrational speech (frontal lobe

inertia).

Brief

notes on some of the causes of dementia are given below:

Alzheimer’s

disease:

Alzheimer's disease is considered the most common cause (50%). Dementia

often precedes gait disturbances and urinary incontinence. There are

features of cognitive dementia in neuropsychological tests. There is

significant cortical atrophy on CT and MRI. Hippocampal atrophy on

coronal CT is related to Alzheimer’s disease and correlates to poor shunt

response concerning cognitive improvement in suspected NPH. SPECT

reveals diminished uptake in temporoparietal

areas.

Vascular

dementia: Formerly known as multi-infarct dementia (MID).

Results from brain damage caused by multiple strokes (infarcts) within

the brain. Symptoms can include disorientation, confusion and behavioral

changes. Vascular dementia is neither reversible nor curable, but

treatment of underlying conditions (e.g., high blood pressure) may halt

progression. There may be superficial cortical and/or deep lacunar

infarcts on CT-scan or MRI. Normal radiology does not rule out

vascular dementia.

Parkinson's disease: A disease

affecting control of muscle activity, resulting in tremors, stiffness and

speech impediment. In late stages, dementia can occur, including

Alzheimer's disease. Parkinson drugs can improve steadiness and control,

but have no effect on mental deterioration.

Pick's disease: A rare brain

disease that closely resembles Alzheimer's, with personality changes and

disorientation that may precede memory loss. There is atrophy of frontal

poles and temporal poles on CT-scan or MRI, and diminished uptake in

frontal lobes in SPECT. It is difficult to differentiate from

Alzheimer’s disease. As with Alzheimer's disease, diagnosis is difficult,

and can only be confirmed by autopsy.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD):

A

rare, fatal brain disease caused by infection. Symptoms are failing

memory, changes in behavior and lack of muscular coordination. These are

features of cortical dysfunction. EEG shows periodic synchronous

discharge.

Lewy body dementia (DLB):

Also

referred to as DLB (Dementia

with Lewy Bodies). A disease recognized only in recent years,

in which the symptoms are a combination of Alzheimer's disease and

Parkinson's disease. Usually, dementia symptoms are initially present

followed by the abnormal movements associated with Parkinson's. There is

no treatment currently available.

Huntington's disease: A hereditary

disorder characterized by irregular movements of the limbs and facial

muscles, a decline in thinking ability, and personality changes. In

contrast to Alzheimer's, Huntington's can be positively diagnosed, and

its movement disorders and psychiatric symptoms controlled with drugs.

The progressive nature of the disease cannot be stopped.

Binswanger's disease: An extremely

rare dementia marked by loss of memory, mood changes, abnormal blood

pressure, and disease of the heart valves or large blood vessels in the

neck. Other symptoms may include tremors, difficulty walking,

incontinence and depression. Binswanger's is slowly progressive, often

marked by periods of partial recovery, and is not at present curable.

There is diffuse periventricular hypodensities and lacunar infarcts on CT

and MRI.

Progressive

supranuclear palsy: There is pseudobulbar palsy and rigidity with

vertical gaze paresis and impairment of convergence. In a later stage

horizontal gaze paresis and downward gaze pareis. On CT-scan and MRI,

there are hypodensities in different anatomical regions such as the

substantia nigra and superior colliculli. In addition, there is atrophy

of mesencephalon and pons, later followed by distension of the aqueduct

and fourth ventricle and atrophy of temporal lobes.There is diminished

uptake in frontal lobes with normal cortical uptake in SPECT.

Depression:

A

psychiatric condition marked by sadness, inactivity, difficulty with

thinking and concentration, feelings of hopelessness, and in some cases,

suicidal tendencies. Many severely depressed persons also display

symptoms of memory loss.

Dementia related to depression,

alcoholism, drug interaction, thyroid and other problems may be

reversible if detected early.

|

Investigations:

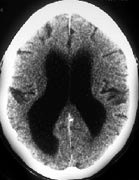

CT scan is the

primary mode of investigation and shows dilated ventricles with normal

sylvian fissures and sulci. Periventricular low density suggests

transependymal flow.

MRI may provide

additional information of the cerebral parenchyma. CSF flow changes may

be studied in MRI. Even if there is some degree of cerebral atrophy,

shunting may help.

Further

tests are normally required if CT and MRI are inconclusive.

|

|

|

|

NPH- CT

|

|

Lumbar

CSF drainage

of about 50ml may help in evaluation; clinical improvement after CSF

drainage implying good response to shunting. This test is not always

reliable, but most commonly employed.

CSF

absorption test,

first described by Katzman and Hussey in 1970, helps differentiate

between presenile dementia and NPH. Saline infused into the lumbar

subarchnoid space at a rate of approximately twice the normal rate of CSF

formation produces a slow rise in CSF pressure in patients with normal

absorption capacity. But when the CSF absorption is delayed as in NPH,

the CSF pressure rises suddenly which predicts good response to a shunt

procedure.

Isotope/contrast

Cisternography

helps to study the CSF circulation. The most commonly used isotope

is iodine 131-labelled human serum albumin (RiHSA). The isotope is

introduced into the lumbar intrathecal space. Normally, activity will

appear within the cisterna magna after half an hour; after about two

hours activity will appear in the basal cisterns and after about 6 hours

over the cerebral hemispheres. By 24 hours the activity is

concentrated in the parasagittal region. Normally visualization of the

ventricular system will not occur. By 48 hours only slight diffuse

activity is generally evident, and symmetry of distribution on

anteroposterior views is the rule. This test is of no use in

non-communicating hydrocephalus. Isotope cisternography in NPH is

characterized by cisternoventricular reflux, lack of isotope in the

anterior basal cisterns, and delayed clearance from the ventricles. Water

soluble contrast, instead of an isotope, helps in a more precise

evaluation.

SPECT scan (single

photon emission computerized tomography) may reveal global diminished

uptake, suggesting a global hypometabolism, in NPH, and help to

differentiate from other causes of dementia.

Xenon

enhanced CT

scan provides a method for cerebral blood flow (CBF) measurement. The xenon

concentration within brain is determined from the CT scans collected

during a 6 minute xenon inhalation. The CT scans enhance with time,

and xenon concentration can be calculated by subtracting the values of

the enhanced scans from the baseline CT. In NPH the regional cerebral

blood flow is decreased in the hippocampal regions and in the frontal and

parietal white matter.

Continuous

ICP monitoring may

predict the outcome of shunt surgery. Those who show transient

increases in ICP (Lundberg B waves) on 24 hours monitoring do well

after a shunt surgery, while those with a flat tracing do not.

Treatment:

CSF

drainage through a ventriculoperitoneal or ventriculoatrial shunt gives

good results. Acetazolamide 250-500/d decreases CSF production and seemed

helpful in one small uncontrolled study. Occasional reports claim no

benefit with shunt.

Some

surgeons prefer to use a low pressure shunt. Others recommend a medium

pressure shunt.

The

mental symptoms improve rapidly and the improvement continues for weeks.

Gait takes a longer time.

In

some cases, improvement after shunting may be delayed for several weeks

to months. In some cases, for unknown reasons, improvement is only

temporary.

On

the basis of numerous studies, in patients with a known etiology and the

complete clinical triad, improvement after shunting will occur in 60-75%

of cases. In idiopathic NPH, this percentage drops to 10-40%.

Postoperative

reduction in ventriculomegaly is not always seen or proportionate to the

clinical improvement. However, there is increased CBF in both grey and

white matter following the surgery.

It

is interesting to note that good outcome following a shunt has been

reported in degenerative brain diseases without all the classical

features of NPH. The presence of atherosclerotic changes does not

influence the results; however, careful selection of patients is

warranted before shunt surgery.

The

following factors suggest a favorable outcome:

1)

Shorter duration of symptoms.

2)

Presence of urinary incontinence and early onset of gait abnormalities.

3)

CT-scan: ventricular enlargement with minimal or absent cortical

atrophy. Enlargement of the third ventricle is also predictive of

good response to shunt.

4)

MRI-scan: A distinction can be made between shunt responsive NPH

(true NPH) and shunt refractive NPH (false NPH) on the basis of T1 and T2

of the water proton of the perventricular white matter. In the true

NPH group both T1 and T2 of the periventricular white matter are

significantly prolonged. In the false NPH group there is only a

significant prolongation of T1. Pronounced aqueductal flow void

extending into the 3rd and 4th ventricle is an

indicator of increased (hyperdynamic) aqueductal CSF flow and shunt

responsive NPH syndrome.

5)

A good response to Lumbar CSF drainage.

6)

Altered CSF dynamics in 24hours CSF pressure monitoring.

7)

CSF levels of delta sleep inducing peptide (DSIP), peptide YY (PYY) and

somatostatin (SOM) are decreased in NPH. Levels of DSIP, SOM and

VIP (vasoactive intestinal peptide) increase significantly in parallel to

the clinical improvement after the shunt operation in NPH patients.

|